Allegany County is located in upstate New York. This is a small county with a population of not quite 50,000, one with significant assets.

- A highly skilled population, especially as compared to other rural areas, with a concentration of tradespeople and advanced manufacturing competence

- The presence of both advanced manufacturing and science-based businesses as well as lower-tech “craft” businesses such as artists and small-scale agriculture

- Deeply affordable – both in terms of housing and overall business costs – as compared to other more urban areas in New York and Pennsylvania

- A region of natural beauty, rich in a variety of outdoor recreational offerings

- Strong anchor educational institutions (Alfred State, Alfred University, and Houghton)

- A strong sense of pride and the willingness to collaborate across the towns to advance the best interests of the county as a whole

Like so much of rural America, Allegany County has been struggling to figure out how to use the assets it has to build out its future self.

Threats to the future include: a declining and aging population, a lack of ethnic diversity, and economically, an overdependence on a small number of large employers in a narrow range of sectors. You can see how these threats are starting to play out by looking at this detailed profile in Data USA.

We worked with ~20 community leaders to craft a program to overcome these threats to the future and-at the same time-leverage the county’s many strengths. Our engagement happened over 3 days and included a 1/2 day of “economic tourism”, followed by a full-day co-creation session which we facilitated, and then a 2-hour debriefing session hosted at Otis Eastern Services LLC.

As we worked with the Allegany County community leaders, three things became apparent.

1. DON’T WRITE OFF RURAL AMERICA

In many ways, the best of America and American values can be found in small towns like Alfred (population: 5,200), Angelica (population: 1,400); Belmont (population: 1,000); Wellsville (population: 7,400). Allegany County is one of the few places in the country where young people can earn enough to buy their own homes. This is not a trivial matter.

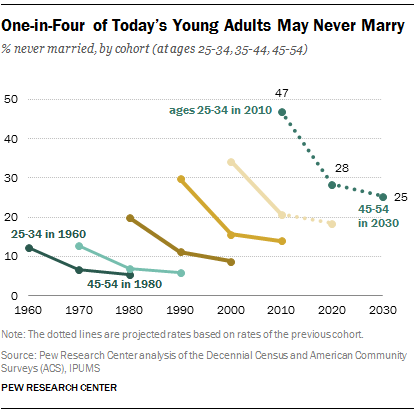

Today’s young adults are slow to tie the knot, and a rising share may end up not getting married at all. According to Pew Research projections based on census data, when today’s young adults reach their mid-40s to mid-50s, a record high share (25%) are likely to have never been married.

Housing prices and job instability are two factors that are thought to explain these trends.

Yet rural areas like Allegany County can provide low-cost housing and relative job stability.

The figures bear this out. In Allegany County, the average salary is $44,085 – which may seem low. But, at the same time, the median home price in Allegany County is $72,100. These two numbers make for a housing affordability index of 1.6x where lower numbers are better. Compare this to the average salary and median home price in San Francisco where the average salary is $103,801 and the median home price $1,020,000, resulting in a ratio of affordability of 9.8x.

2. FOR ALLEGANY COUNTY, BUILDING OUT ITS FUTURE SELF MEANS GOING BEYOND ITS INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE

The future of the county is likely to be written in some combination of advanced manufacturing, entrepreneurship, and creative placemaking, the last to make Allegany County more attractive as a place to live but also to nurture the many tourists who travel to Allegany County to hunt and fish and enjoy the ATV trails at Tall Pines. We say this because due to changes in demand for oil and petroleum, the county has been struck by two plant closings. The number of actual jobs affected is small by big-city standards; one plant closing resulted in 100 jobs lost, one resulted in 350 jobs lost. Still, even 450 jobs lost has a ripple effect on the county, where the average town has a population of around 5,000.

3. INFRASTRUCTURE MATTERS

Time and time again we heard that the County was stymied by a lack of infrastructure. High bandwidth internet access exists but is not readily available to startup businesses. There’s an incubator but its short staffed, so you cannot just “drop in”, but must make an appointment to access its resources. There’s no coworking space in town. Also, the entire county is served by just one hotel although that will change later this year. Professional services are thin on the ground and in part, this is attributed to a lack of professional-style housing (apartments and condominiums versus standalone homes). Together, this lack of infrastructure is making it increasingly difficult to attract and retain newcomers to the area. Some cities and towns are starting to deal with this by paying people to move to the area. This is an expensive proposition and one that could backfire if the people who move there don’t end up staying for the long term.

THREE BUILDING BLOCKS FOR THE FUTURE OF ALLEGANY COUNTY

Advanced Manufacturing

Allegany County is home to many advanced manufacturing firms. This didn’t happen accidentally, it is part of the county’s heritage thanks to the presence of Alfred State College and Alfred University. While Alfred University is known across the world for its ceramics program, Alfred State College (part of the SUNY system) is also a key conduit of talent, attracting about 30% of its students from the five boroughs of New York City, who come there to attend its 2-year programs in the building trades and in mechanical engineering.

Some students end up working at Otis Eastern, Siemens|Dresser/Rand*, or the Arvos Group – ljungström division, three of the biggest employers in the county.

Otis Eastern serves many roles in the community. It is one of the largest local employers, a key source of local philanthropic investment through its founder Charles Joyce, and home to the Mayor of Wellsville – Randy Shayler – who works at Otis Eastern as Director of Resource Management. Multiple roles like this are part and parcel of working in the County, with many county legislators and economic development officials holding part-time appointments at the local universities. As we’ve written about elsewhere, due to the high cost of living, many rural areas are finding they can attract native sons (and daughters) like Charles Joyce to set up shop locally. Investing first in building a strong business that employs people locally, then investing in the development of the kind of civic institutions that can make a small town thrive as well as new forms of housing which are necessary to attract and retain professional workers.

Entrepreneurship

One of the many highlights of the trip was visiting Northern Lights, founded by Andy and Tina Glanzman, who moved to Allegany County from New York City, for lifestyle reasons. Andy Glanzman, CEO and Founder, gave us a tour of the facility, which is the largest employer not just in Wellsville, NY but also in Allegany County as a whole. Northern Light makes candles, the kind of candles that are then labeled by some of the biggest brands in the U.S. and then sold through major retailers, department stores (remember them?), and gift shops.

Northern Lights is the kind of artisanal business that we think could thrive in small, rural communities across America. Firms like this build up both process expertise and a skilled workforce. According to Northern Lights, the average employee has been with them for 18 years. In our tour, we met several employees who started out on the assembly line and are now running entire departments. Some come to Northern Lights with degrees in chemistry from one the three local universities (Alfred State, Alfred University, Houghton College).

Creative Placemaking

Andy is also the investor and founder of the Wellsville Creative Arts Center (WCAC), located in downtown Wellsville, which while not the county seat might as well be. (The actual county seat is Belmont which is located in the geographic middle of the county but is not nearly as vibrant a place as Wellsville). The WCAC is where to go to see music, hear local people speak about their passions at Open Mic night, and learn or improve your skills as a ceramicist. Ceramics is “baked in” to the DNA of the place thanks to Alfred University’s program and the county’s single incubator, Incubator Works which is funded – in part – by Corning – and started out with a focus on ceramics and has since expanded to include more types of businesses.)

What we loved seeing was the passion of a local entrepreneur who not only built a nationally-recognized business from scratch that employs people for the long term (Andy told us that the average tenure at his company is ~18 years) but also is investing in downtown Wellsville, having created not one but two civic institutions from scratch. In addition to Wellsville Creative Arts Center, Andy just purchased land on Main Street and is turning it into a labyrinth.

The labyrinth (still under constructed; the image above is what the labyrinth may look like when finished … although Andy plans one that uses bricks more so than grass, for ease of maintenance) resonated with us as a form of creative placemaking; also because we are familiar with the two labyrinths at Grace Cathedral here in San Francisco.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CITIES

The Maker City story is increasingly one of American reinvention, with similar themes and tactics resonant across the landscape. When we began this project we called it “The Maker City” because we thought that was where the action was. Not quite right. We should have called it “Maker Cities, Towns and Hamlets” because it’s increasingly clear that towns of all sizes are adopting the innovation playbook and the bottom-up spirit of the Maker movement in a myriad ways appropriate to their local context and heritage. This is the jubilant spirit of renewal that James Fallows chronicles in the book Our Towns, his recent epic 100,000 mile journey across America. America’s secondary cities are all-at-once showing renewed momentum, building on their affordability, their legacy downtown cores, and contemporary efforts to attract and retain talent. The great lingering question is: in this age of urbanization, what about rural areas, how do they spring back, what works in this time of enormous technological and economic change? It’s in places like Allegany County New York where questions like these are most restlessly alive, which is why we felt so privileged to help that region explore its future.

Originally published on the Maker City blog.